‘Pakistan holds the key to Afghanistan’

The end of the American intervention in Afghanistan has turned into a rout with the recapture of Kabul by the Taliban and the flight of president Ashraf Ghani. As an expert on the country, anthropologist Pierre Centlivres, gives his assessment of the situation.

Stunned by the attacks of September 11, 2001, the US declared a “war on terror” with a large-scale military operation targeting the bases of Al-Qaeda led by Osama Bin Laden and also the Taliban regime that had ruled Afghanistan since 1996.

The US and their allies combined their military operations – which officially ended in 2003 – with a campaign of “nation building” to lay the foundations of a democratic state. What progress was established, notably the emancipation of women, is now in doubt due to the probable return of Islamic law with the Taliban.

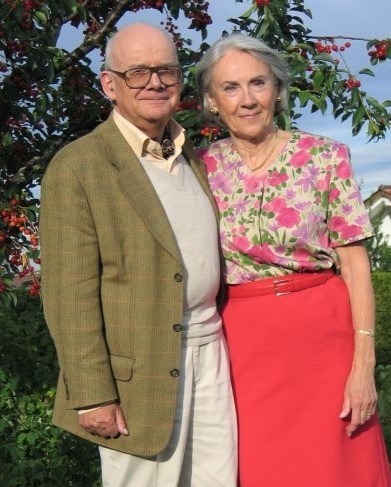

A prominent member of the Institute of Anthropology in Neuchâtel, Pierre CentlivresExternal link has researched a great deal on Afghanistan. Together with his wife, Micheline, who is also an anthropologist, he has published several books endeavouring to explain the country and its people.

SWI swissinfo.ch: Was this failure of the US and NATO inevitable?

Pierre Centlivres: The goals of the US and NATO were never very clear. Were they trying to fight terrorism and capture Bin Laden, or give the country a constitution and build a democracy? The whole military operation embraced these different aspects of the conflict. After the events of September 11, Washington called on the Taliban to hand over Bin Laden. They refused. This negative response was the trigger for the American intervention.

SWI: Both on the military and civilian levels, the 20-year intervention seems to have failed completely. Why is this?

P.C: In my view, there are several factors that explain this failure. First of all, the American military operation was based on false premises and a poor analysis of the situation, as is shown by Washington’s objectives. Secondly, there is also the failure of the war against the Taliban, who have been steadily gaining ground since 2003. These failures were compounded by the poor performance of the Afghan government at all levels, including the governors of the different provinces.

In the last government, there was great disunity among the different ministers, and also between President Ashraf Ghani and his opponent in the presidential election, Abdullah Abdullah. These divisions grew against a background of generalised corruption. The officials appointed by the president, especially the governors of provinces or police chiefs, expected to enrich themselves in office.

SWI: The Afghan army offered almost no resistance to the final offensive of the Taliban. How do you explain this?

P.C: Corruption has sapped the integrity of the army too. Many soldiers were not being paid, because their officers had pocketed the money. The numbers of men in fighting units were inflated, so as to qualify for American money advanced to equip these non-existent units. Also, many of the soldiers were uneasy about fighting the Taliban. These were compatriots, who shared in their Islamic faith, and who just happened to be opposed to the government. So an Afghan soldier might well wonder: why fight my brothers and fellow Muslims?

SWI: What part have non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in this debacle?

P.C: Many NGOs from Western countries, and from the Arab states as well, were on the ground in Afghanistan. These NGOs did good work, building roads, hospitals, schools, training centres, and so on. But a good number of them couldn’t manage to coordinate their projects. They brought a lot of money with them, and there were benefits for local figures. Without intending to, the NGOs became a source of corruption.

It must be said, their contribution was also positive. Afghanistan is nothing like what the country was in the 1990s. A whole range of progress has been achieved.

SWI: Now that the Taliban are back in power, can we expect an end to the hostilities, or is there going to be another civil war as when the Soviets withdrew?

P.C: The Taliban aim to achieve international credibility and do not want to antagonise their neighbours. But I don’t think that means peace and goodwill are going to settle over the country just like that. There are likely to be several regions that are not eager to accept the authority of the Taliban, namely in central Afghanistan, Hazarajat and Panjshir.

Then again, let us not forget that the Taliban are not the only ones with a thirst for power. On the extreme Islamist wing, there are groups that have established themselves in Afghanistan and which might engage in hostilities against a Taliban government. There are also dissident factions in the Taliban movement itself. There may be rebel warlords too who will not be willing to give up the power they enjoy.

SWI: Prominent members of the civil society that has developed in the past 20 years have been murdered in recent months. Is this another reason for us to expect the worst ?

P.C: The measures adopted by the Taliban from 1996 onwards were pretty brutal: no music, no pictures, restricted internet, women were forbidden to go out except with an escort and completely veiled, girls’ schools were closed and so on. These sorts of measures may well be on their way back. The Taliban even made Hindus wear a yellow emblem, though this was soon abandoned due to international indignation.

SWI: Since the 1970s, AfghanistanExternal link has not been able to transform itself into a lasting modern state. Is there a factor there that explains the instability, violence and warfare the country has undergone for over 40 years?

P.C: That’s a hard question. There are significant divisions in Afghanistan which make it difficult to achieve modern statehood. For example, the recent constitutions centralised power while the Afghan regions were demanding more autonomy. I think too that there are contradictory demands coming from apologists of the pure Islamic lifestyle (not just among the Taliban) and those in favour of a more powerful state and a legal system independent of Sharia law. So there are dividing lines between regions and tribes on the one hand, and the logic of statehood on the other.

SWI: Can Afghanistan’s neighbours be a force for peace in the country, or will they aggravate the rivalries and antagonisms within Afghanistan?

P.C: Pakistan has covertly been aiding the Taliban and encouraging their advance. So as not to be outflanked, Islamabad wants to keep Afghanistan separated from India, which has been opening consulates and running a series of projects inside the country.

The former Soviet republics like Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan fear the influence of Islamist groups which might use Afghanistan as a springboard to foment instability in their countries. Iran provided aid to the Taliban locally, but only to hit back at the Americans. Basically, Iran will not be supporting the Taliban, who are fiercely Sunni. Tehran may want to block any large-scale Afghan emigration onto its territory.

The Chinese have an interest in mining the Afghans’ natural resources, such as copper. So I think they will try to maintain good relations with the Taliban without preaching or imposing any political ideology.

Pakistan has the real key to the situation. The country controls the routes between Kabul and ports like Karachi. The key elements of trade go through Pakistan and Iran.

Translated from French by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.