Switzerland’s exclusive democracy

Since the creation of the Swiss federal state in 1848, the number of people who have become eligible to vote has risen steadily. But it has been a long and bumpy road.

Back in the 19th century, with cold-blooded calculation, the bourgeois elite in Switzerland’s federal and cantonal governments did everything in their power to deny their political enemies voting rights. They were amazingly creative and did their best to slow the integration of many marginalised groups.

Conservative Catholics and the poor were the particular targets of their exclusion measures. To prevent poor people from being integrated, the bourgeois elite focused on the Social Democratic Party, which was established in 1888 to defend the interests of the working class.

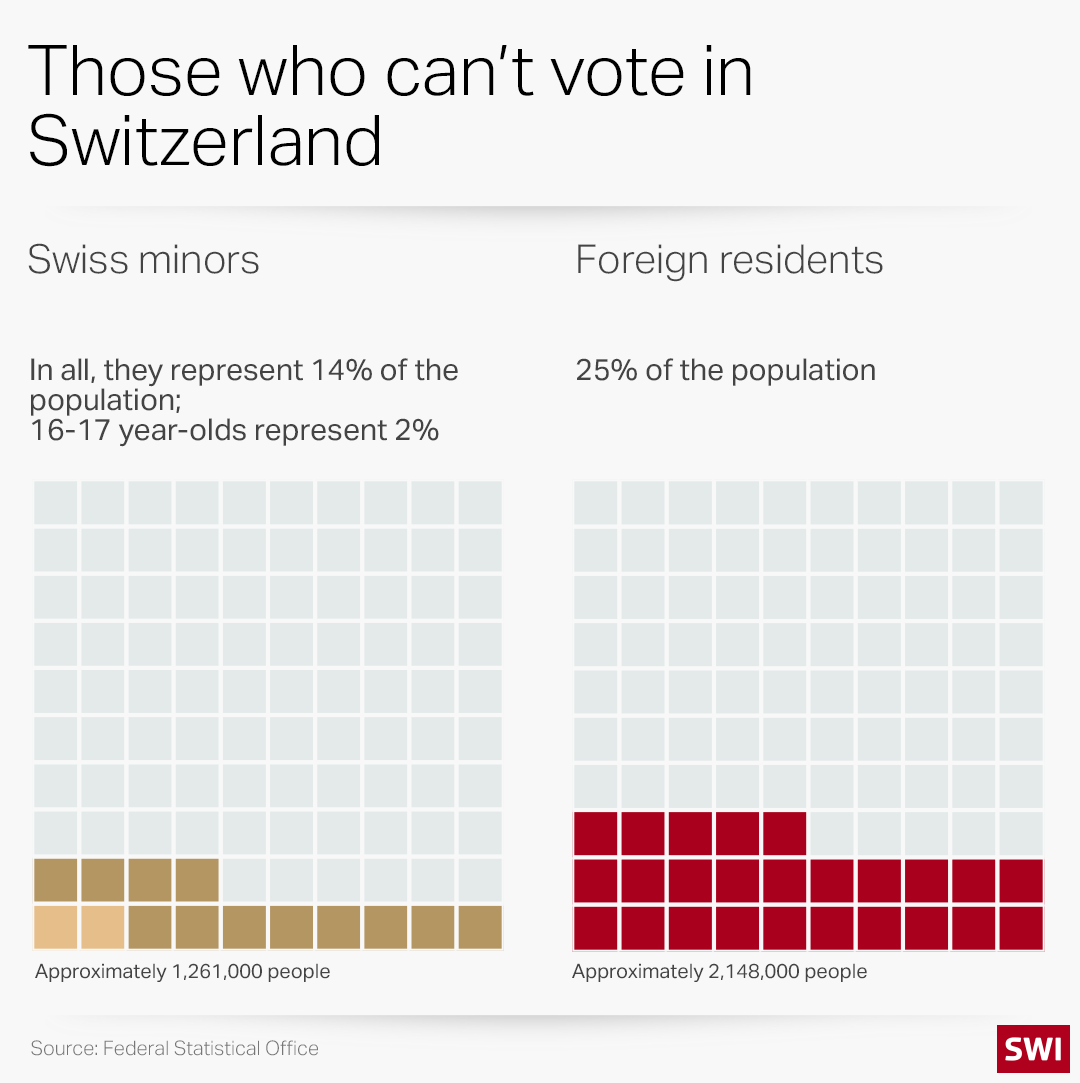

When the modern Swiss state was created in 1848, it initially only granted voting rights to men over 20 years old. Women, who made up half the population, were excluded.

This meant that only 23% of the population were eligible to vote – Switzerland was only a ‘quarter of a democracy’, at best. Where were the others? Where was the other half of the male population?

The Swiss Constitution states that two conditions must be met for a citizen to be eligible to vote at the federal level: freedom of establishment and a tax-payer. Jewish residents, who were forced to live in two communities until 1866, and the poor, who could not pay taxes, were excluded.

Cantons’ freedom to act

In the Swiss federal system, the cantons have sovereignty over electoral laws rather than the federal authorities. Over the years they have administered them in an arbitrary fashion. They created long lists of groups who were denied voting rights: the poor, people whose businesses went bankrupt or who had their properties seized, convicted criminals, those detained without trial, the mentally ill, the mentally weak, and those considered “immoral”. Male residents from other cantons, so-called internal migrants, were also not allowed to vote.

Some of the cantons even went further. The cantons of Bern, Schwyz, Fribourg, Solothurn and Aargau excluded men who had been banned from entering pubs, those considered ruffians, drunks or swindlers. Geneva and Neuchâtel excluded mercenaries, while canton Solothurn banned vagabonds. Ticino also refused to grant voting rights to electoral fraudsters.

“If it had not been up to the male population to decide on who gains voting rights but to the government, women’s suffrage would have been introduced a lot earlier,” said Adrian Vatter, professor of Political Science at Bern University.

“When it comes to granting new groups voting rights, it is a paradox that exclusion and slow integration prevail in direct democracies while there is accelerated process in a representative democracy,” Vatter explained.

Basically, when it comes to the fundamental democratic right of integration, representative democracies are more democratic than the ever-so-democratic direct democracies.

The Catholic canton of Appenzell Inner Rhodes excluded men with “insufficient religious education”. This was a way for politicians to shut out non-believers, or anyone else they wanted to get rid of.

In the poor mountain canton of Valais, people who turned down an inheritance did not have a vote either. Those who did not want or were unable to pay off their fathers’ debts were punished by being deprived of their voting rights. Thus, voting rights were reserved for the wealthy and more fortunate.

The federal government eventually decided that something needed to be done about the various cantonal regulations of exclusion. In the totally revised Constitution adopted in 1874, the federal government in Bern took away the cantons’ rights to choose who to exclude. However, it took a long time to implement the changes as the new law met stiff opposition. Parliament rejected it three times – in 1875, 1877, and in 1882.

The practice of excluding people because of their religion, social status or gender remained in place up until the end of the 20th century. In 1915, the Federal Court declared that excluding people for tax reasons was unconstitutional, however, it still supported the exclusion of the poor. It was not until 1971 that condemned criminals and people in debt gained the right to vote.

123 years for three stages

The shift from exclusion to integration began in 1874.

According to political scientist Adrian Vatter, this was the start of a pattern of development.

“There was an ongoing integration process, which ran in parallel to the expansion of power-sharing institutions, and which also took place alongside social changes occurring at the end of the 19th century,” he said.

Vatter said three stages were instrumental in the process. The first stage was the introduction of popular rights such as referendums and people’s initiatives. These were launched in 1874 and 1891, respectively, and included religious groups like the conservative Catholics. The second was the introduction of proportional representation in 1919, which gave the working class and the Social Democrats a voice. The third and last stage was in 1971 when women were granted voting rights.

“All integration processes were accompanied by an emancipation process,” said Vatter. In 1977, Swiss citizens living abroad were granted voting rights, while the 18-to-20-year-olds were allowed to vote for the first time in 1991.

Male democracy as revolution

How did Switzerland fare in the integration process? Vatter stresses that voting rights for men marked the beginning of the long road to making Switzerland more democratic.

He pointed to the election of Geneva’s cantonal government in 1847 by Swiss male citizens who had voting rights. “Today it is common practice that a nation elects its government; back then it was a European first,” he declared.

Back in 1848, Switzerland was a democratic island with voting rights for men in the middle of a European sea of authoritarian and monarchist regimes, said Vatter.

“It was a big step to grant a quarter of the population voting rights,” he added.

Drawing the line

Looking at the current situation, Vatter’s assessment is rather ambivalent. “On the one hand, Switzerland is considered a paradigmatic case of political integration. Given its different cultures and diverse society, it has managed to integrate various minorities,” he said.

“However; Swiss integration efforts are strictly limited to groups from their own circles, i.e. to people who speak the same language and follow the same religion.”

Vatter draws the line when it comes to foreign populations with other languages and fundamentally different values. “This is why the introduction of voting rights for foreigners does not stand a chance at the national level. In a united Europe, however, voting rights for foreigners is common practice, at least at a communal level.”

Cantonal pressure

Vatter believes a total revision of all cantonal constitutions is the only way to change and eventually introduce voting rights for foreigners. But putting this issue to a referendum will stand a chance only if the cantons put pressure on the government.

The time is not ripe yet for giving foreigners the vote. Youngsters, who are still not allowed to go to the polls, have a better chance. Inspired by the climate strikes and the Green Party’s historic success in the 2019 federal elections, some young politicians have been calling for lowering the voting age from 18 to 16. That has a better chance of happening than foreigners getting the vote. They are a popular group as they speak the right languages and own the right passport.

At national level, the only way to gain voting rights is to apply for Swiss nationality. However, the path to securing Swiss passport can be long and bumpy for foreigners. The process takes a long time, it is expensive and often arbitrary as it is up to the communes to decide whether someone gets citizenship or not.

Five Swiss cantons, mainly in French-speaking regions, grant non-Swiss citizens the right to vote. However, this is only possible at the cantonal and municipal levels. About 600 of Switzerland’s 2,022 communes grant foreigners voting rights.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.