The Swiss terrorist who worked for the CIA

Swiss left-wing extremist Bruno Breguet belonged to the notorious terrorist group led by Carlos the Jackal. New evidence shows that Breguet ended up as an agent for the CIA, the US intelligence agency.

On November 12, 1995, Breguet disappeared from a ferry in the Mediterranean. The day before he had been refused entry at the port of Ancona. As a known political extremist, he wasn’t welcome in Italy. Breguet was forced to sail back to Greece – witnesses saw him on board that night. But when the ship docked in Igoumenitsa the next day, he was missing, and rumours and speculation soon spread about what had happened to him.

Who was this largely forgotten native of Ticino, southern Switzerland, whom the Swiss media still described in 2003 as a “top terrorist”?

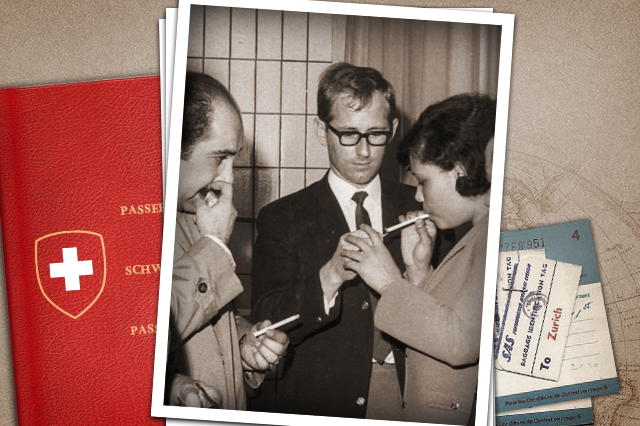

Breguet, born in 1950, grew up in Minusio on the shores of Lake Maggiore. In February 1969, when the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) launched an attack on an airliner belonging to Israeli airline El Al at Zurich airport, the Middle East conflict suddenly came home to Switzerland.

More

The day Palestinian militants attacked Zurich Airport

As the perpetrators went on trial in Winterthur, Breguet went through a process of radicalisation. He came to view the fate of the Palestinian refugees as a monumental injustice. Like many of the 1968 generation he read Mao and Che Guevara, and he saw the Palestinian fighters as a vanguard on the way to world revolution.

In 1970 Breguet travelled to Lebanon and received military training at a camp run by the PFLP which was supposed to prepare him for a mission in Israel. Breguet had volunteered for a bomb attack. The target was the Shalom Tower, a Tel Aviv landmark and at the time the tallest building in the Middle East. But the Israelis caught him in the port of Haifa with two kilogrammes of explosives. A military court sentenced him to 15 years in jail.

By 1977 Breguet was free again. His early release was due to diplomatic initiatives by the Swiss government but also to an international campaign of solidarity that was supported by literary figures such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Günther Grass, Max Frisch and Friedrich Dürrenmatt.

In league with the Jackal

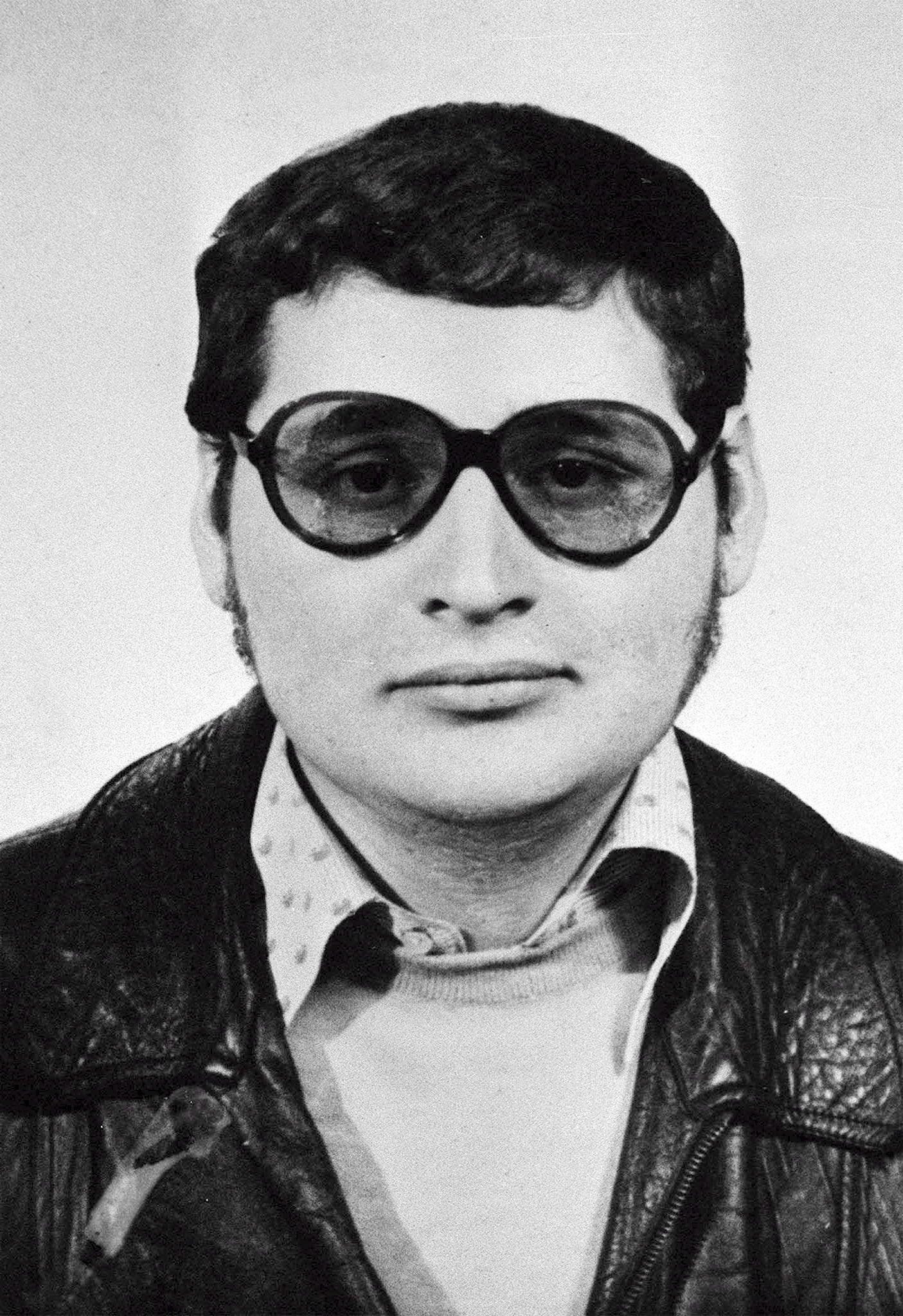

Determined to resume the armed struggle, Breguet later joined the group led by Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, known as Carlos the Jackal. The Venezuelan had been the world’s most wanted terrorist since 1975, when he led a commando raid on the offices of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in Vienna and took 11 oil ministers hostage. By the end of the 1970s he was able to start his own terror organisation, which he recruited mainly from former PFLP fighters and left-wing extremists from the Revolutionary Cells group in West Germany.

In league with the Jackal, Breguet’s ideals soon evaporated. Carlos’s group was officially dedicated to the cause of world revolution and proposed to “make war on imperialism in all its forms”, as the Stasi, the East German secret police, noted. But it was really more like a criminal gang with a revolutionary veneer. The prime aim was to amass a fortune through protection racketeering, gun-running and contract killings on behalf of Arab despots.

Carlos and his friends even found themselves working for the Romanian secret service. In February 1981 his organisation, together with extremists belonging to the Basque group ETA, launched a bomb attack on Radio Free Europe in Munich. This American propaganda station broadcasting to the countries behind the Iron Curtain was an annoyance to the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu in particular. Top-secret documents from Eastern European archives and statements from a former comrade later incriminated Breguet. It seems he was the one who remotely detonated the bomb. It was sheer good luck that no one was killed.

‘Breguet will not serve his sentence’

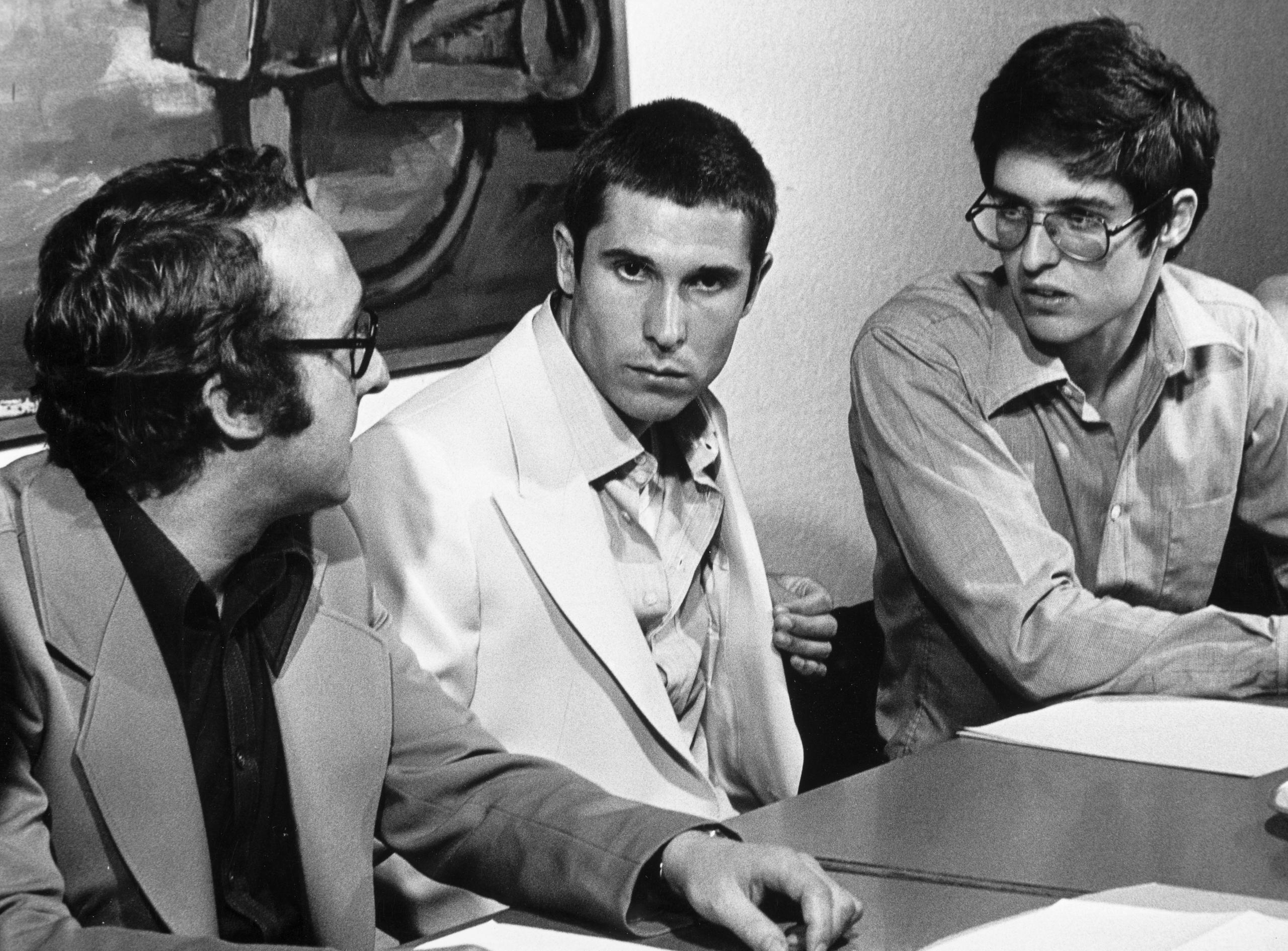

When he tried to carry out another bomb attack in Paris in 1982, Breguet was arrested. Carlos tried to get his man freed by sending the French interior minister a threatening letter with an ultimatum.

Breguet’s lawyer Jacques Vergès was confident. “You know it, he knows it, the government knows it – even if Breguet is found guilty, he’ll never serve his sentence. We know it. The question is how long it will take before he is released. That is, how many deaths it will take, inflicted by his friends on the French authorities, until they are ready to let him go.” The answer turned out to be three-and-a-half years, at least 11 dead and 139 injured by the time Breguet was released.

The French government let the ultimatum expire and Breguet was sentenced to five years in prison together with Magdalena Kopp, one of the leaders of the terrorist group and later Carlos’s wife, who was alleged to have assisted Breguet in the Paris attack. Carlos now declared all-out war on France. There was a wave of brutal attacks which cost the lives of many civilians. But the government in Paris was adamant. Breguet had served two-thirds of his sentence by the time he was deported to Switzerland.

From terrorist to CIA agent

In the years that followed, Breguet operated as a kind of deputy leader for Carlos’s gang in Western Europe. The Jackal and his closest comrades-in-arms had to hole up in Damascus, because Communist regimes in Eastern Europe were no longer willing to tolerate their presence. Breguet, who was legally a resident of Ticino, often spent weeks at a time in the Syrian capital.

What was unknown until now is that one day in the spring of 1991 the self-styled “professional revolutionary” slipped into an American embassy and offered to betray his organisation. Documents in the US National Archives show that Breguet worked for the CIA under the alias “agent FDBONUS/1”. For a monthly retainer of $3,000 (about CHF6,000 in today’s money) he passed on to the Americans all the secrets of Carlos’s gang: operational details, arms dumps and networks of support.

By September 1991 the Syrian government had also had enough of Carlos and expelled him and his last faithful henchmen from the country. Carlos, the “world’s most dangerous terrorist”, now embarked on an odyssey through the Middle East. He stayed for a time in Jordan, and then in the Sudanese capital Khartoum. Breguet now had a key role in the CIA’s plans to track down the Jackal. In 1994 American agents finally found Carlos in his Sudan refuge. He was captured and turned over to the French government.

The revenge of Carlos?

The revelation that Breguet ended up as a CIA agent casts a new light on his mysterious disappearance. Did the CIA help him start a new life under a new name? Breguet’s usefulness as an agent may have decreased by autumn 1995. At that point Carlos and his right-hand man, the German Johannes Weinrich, were both behind bars.

On the other hand, an act of revenge seems obvious. Had Carlos got wind of Breguet’s betrayal and was he out for vengeance, even in his Paris prison cell? It’s entirely possible, for the structure of the group was still intact enough in November 1995 for Carlos to put out a contract on someone. He had his channels of communication to his henchmen on the outside; in Lebanon, there were still contract killers ready to work for him and his war-chest was well stocked. Or did Breguet just do a disappearing act of his own, as the then Swiss attorney-general Carla Del Ponte assumed?

Adrian Hänni is a lecturer in political history at FernUni Switzerland and a visiting scholar at Georgetown University in Washington. As a historian, he researches the history of secret services, propaganda and terrorism. He is author of ‘Terrorist und CIA-agentExternal link: Die unglaubliche Geschichte des Schweizers Bruno Breguet’ (Terrorist and CIA agent: The incredible story of the Swiss Bruno Breguet).

Edited by David Eugster. Translated from German by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.