When the human body becomes a powerhouse

An innovative Swiss startup has developed a technology to transform the heat of the human body into electricity. Could it be that soon we will be able to charge up our personal devices with the power we produce naturally – and at no cost – every day?

Just for a moment, let’s forget about solar, wind, biomass or hydro power: what if a source of renewable energy for the future were to be found in human beings? As we all know, our bodies generate heat. We are particularly aware of this when we are in bed with a fever, or just after strenuous exercise. But this capacity to produce heat distinguishes us from reptiles and other cold-blooded creatures.

It is perhaps not so widely known that human heat can be stored and made into electricity. It’s not a new idea, but in the last few years researchers have been able to develop high-tech power storage devices that can be used for practical purposes. These have a mass market potential in the fields of medicine and “wearable technology” – think smartwatches or fitness bracelets.

Mithras, a 2018 spin-off from the federal technology institute in Zurich (ETH Zurich), aims to carve out some market share in this field. “I’ve always wanted to create something with real potential, and so I got into the technology sector,” Franco Membrini, the founder and CEO of Mithras, told SWI swissinfo.ch. Though he started out doing a master’s degree in history, he was fascinated by the idea of making use of human body heat because he could see from the start “the great potential of this kind of decentralised approach to generating electricity”.

10% of world power from the human body

The thermal energy emanating from the human body is on average equivalent to that produced by a 100-watt lamp.

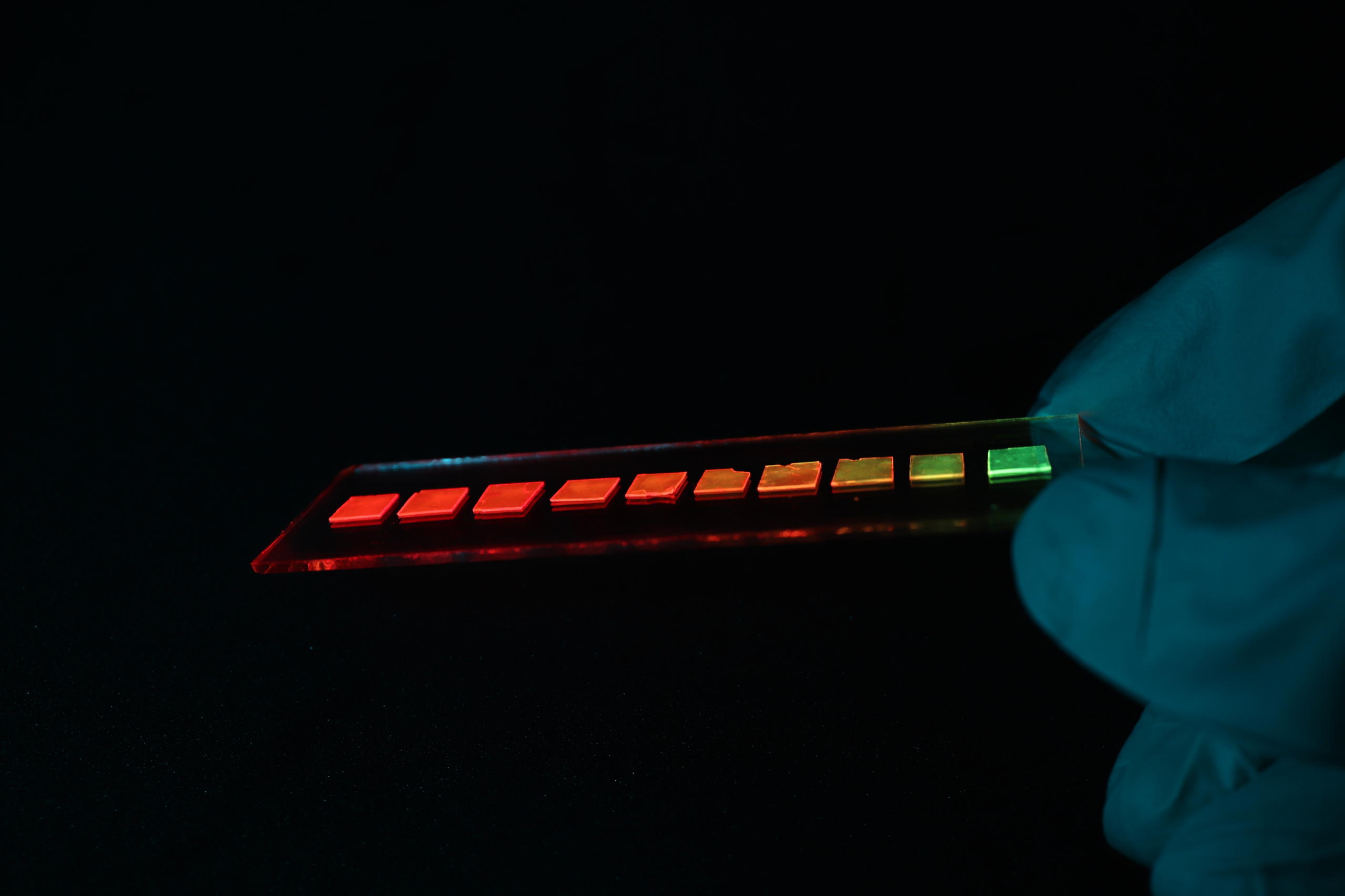

Most of the power just dissipates itself in the surrounding environment, but it is precisely that kind of “waste” which the startup based in Chur in eastern Switzerland aims to recycle. It can do this by means of a thermo-electric generator (TEG) which uses the difference in temperature between the skin surface, about 32 degrees Celsius, and the surrounding environment, so as to generate electricity. This is called the Seebeck effect. To see how it works, watch this video:

“The important thing is the temperature difference between body surface and surrounding environment: the greater this is, the more power will be generated – but it doesn’t matter if you’re in a polar region or out in a desert,” explains Membrini. “All it takes is one degree of difference to start generating electricity.”

It would be impossible to capture 100% of the heat energy coming from the human body and convert it into electricity, he points out, “but these TEGs are a promising strategy and they’ve got enormous potential.” According to Mithras’ calculations, heat generated by the Earth’s seven billion people could provide up to 10% of the power consumed in the world.

A forgotten technology makes a comeback

This idea is not new. Researchers and engineers have been trying to use the human body as a renewable power source since the early 20th century, Membrini points out, recalling hand-cranked radio transmitters from the 1940s. Yet progress in battery technology has, in the meantime, sidelined systems powered by man himself.

Now, thanks to recent developments in materials science and wearable low-frequency devices, power produced by the body has come in for fresh attention. “At Mithras, we started with an existing technology and we made something new out of it,” says Membrini.

The Seebeck effect has been understood for a while, as René Rossi told SWI swissinfo.ch. He heads the study of biomimetic membranes and textiles at EMPA, the Swiss federal laboratory for materials science and technology. “Up till now, the applications and effectiveness of these systems were fairly limited. But now, if the level can be increased from milliwatts to tenths of a watt, it begins to look more interesting from a commercial point of view.”

Currently, he adds, research is progressing in various directions. “For example, we are developing smart fabrics which pick up solar energy. Other research groups are trying to recover mechanical energy and transform it into electricity, integrating generators into the soles of shoes.”

It works while you sleep

Mithras is working on two main ideas: a bracelet TEG to be worn on the wrist which can be used for charging mobile devices, and an integrated solution in which the thermo-electric generator is inserted directly into the device and hooked up to its battery. The only prerequisite to generating electricity is that the device should be in contact with the body, Membrini points out. “It doesn’t matter if you’re having a coffee, engaging in physical activity, or sleeping: the battery charges by itself.”

The Swiss startup has six employees and intends to concentrate mainly on medical devices, given their low consumption of energy. “We would like to make insulin pumps, hearing aids and biosensors monitoring body temperature and vital functions autonomous from an energy point of view,” says Membrini. This would be a way to get around problems due to malfunctioning batteries and possible complications arising from surgery to replace them.

Another possible application would be cellular phones, even though this is not currently a priority for Mithras. “A smartphone consumes too much power compared to our solution. At most we can prolong the life of the battery,” Membrini says.

As the winner of the last edition of Swisstech Pitchinar, a competition among Swiss start-ups geared to the Chinese market, Mithras expects to launch its first product – a biosensor to monitor vital signs – by the end of this year.

“We are in contact with some large international companies operating in the medical technologies sector,” says Membrini. “This is going to be the first device of its kind to operate exclusively with body heat.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.