Swiss look for life on Mars

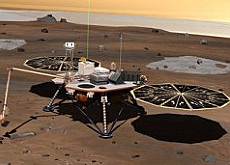

Scientists at Basel and Neuchâtel universities and a Swiss nanotechnology company are part of "Phoenix", Nasa's latest mission to Mars.

They will all be crossing their fingers on Saturday as the journey begins to the Red Planet’s north pole, where the Lander will take soil samples and Swiss technology will help ascertain whether the surface ever contained water.

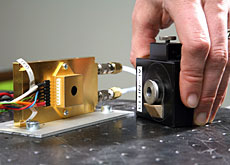

The Swiss contribution to the latest mission is an atomic force microscope (AFM), designed specifically for the tough conditions on Mars.

The microscope was built by nanoscience company Nanosurf, based in Liestal near Basel, and also by electronics expert Hans-Rudolf Hidber at the Basel Institute of Physics and nanotechnologist Urs Staufer at the Neuchâtel Institute of Microtechnology.

One of the mission’s two primary objectives is to look for a habitable zone in the Martian soil where microbial life could exist. The other is to study the geological history of water on Mars.

The Lander has a 2.5-metre robotic arm that can dig a 50cm trench in the soil. The arm is fitted with a camera that will be able to verify that there is soil in the scoop when returning soil samples to the Lander for chemical analysis – overcoming an important design flaw in the Viking Landers of the mid-1970s.

Testing

The craft characterises the soil of Mars much like a gardener, thanks to a Microscopy, Electrochemistry and Conductivity Analyzer (Meca).

By dissolving small amounts of soil in water, Meca determines the pH, the abundance of minerals such as magnesium, as well as dissolved oxygen and carbon dioxide.

Meca also includes a mass spectrometer capable of detecting organic volatile substances down to a ten-thousandth of a millimetre (100 nanometres), in addition to an optical microscope and the Swiss-designed atomic force microscope.

With images from these microscopes, scientists will examine the fine-detail structure of soil and water ice samples. Detection of hydrous and clay minerals by these microscopes may indicate past liquid water in the Martian arctic.

The AFM will provide sample images down to ten nanometres – the smallest scale ever examined on Mars. Using its sensors, the AFM creates a very small-scale “topographic” map showing the detailed structure of soil and ice grains.

“Ice crystals would really be a stroke of luck,” said Staufer, concerned that any ice found could quickly sublime into a vapour before reaching the microscope.

Crash-landing

The Swiss journey to Mars has had its ups and downs.

“Nasa asked us in 1999 whether we were in a position to build an atomic force microscope capable of travelling to Mars,” Staufer said. Nanosurf, a spin-off firm from Basel University was also involved.

Almost unbelievably the Swiss delivered the six units by October 2000 and the world’s first atomic force microscope fit for space was ready for take-off.

However, a spanner was thrown into Nasa’s entire Mars programme when communication with its Mars Polar Lander was lost just prior to entry in December 1999.

As a result of this costly failure – which was most likely caused by the Lander switching off its engines 40 metres above the surface of Mars, thinking it had already landed – programme reforms were instigated and the Swiss microscope’s trip, planned for 2001, was scrapped.

Life?

Then in 2003 the call from Nasa came again, asking whether the Swiss would want to be on board the Phoenix mission.

“It wasn’t easy to repeat our breakneck performance of 2000,” admitted Hidber.

According to Staufer, this was because the mission had a different goal. “Previously the task was to examine the toxicity of dust on Mars with a view to a possible manned mission.”

The goal of Phoenix however is to clarify once and for all whether there is enough water on the planet to sustain microbial life. The truth is out there.

swissinfo, based on a German article by Ulrich Goetz

The Phoenix Mars Mission, scheduled for launch on August 4, is the first in Nasa’s “Scout” programme.

Phoenix is designed to study the history of water and search for complex organic molecules in the ice-rich soil of the Martian arctic.

The mission is an international effort: the project management lies with Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Lockheed Martin Space Systems.

The scientific side is led by the University of Arizona, with contributions from the Canadian Space Agency, the German Max Planck Institute, and the universities of Basel and Neuchâtel in Switzerland and Copenhagen in Denmark.

Switzerland has an annual space budget of around SFr140 million ($115 million) until 2010.

Switzerland’s major recent achievements in space include providing technology for the Rosetta comet-chasing probe, the production of atomic clocks to help navigate satellites, and involvement with the Venus Express probe.

The distance between Earth and Mars fluctuates between about 56 million and 400 million kilometres, as the two planets swing around their respective orbits.

Mars is a cold, dry, desert landscape of sand and rocks. Many land features on the surface of Mars, such as volcanoes, canyons and valleys, make it look similar to Earth, but humans could not survive in the present environment on Mars. The average surface temperature is -63 degrees Celsius, and night-time temperatures can plunge to -110 degrees.

Mars is only about half the diameter of Earth, but both planets have roughly the same amount of dry land surface. This is because more than two-thirds of the Earth’s surface is covered by oceans, whereas the present surface of Mars has no liquid water.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.