Why Swiss women are back on strike today

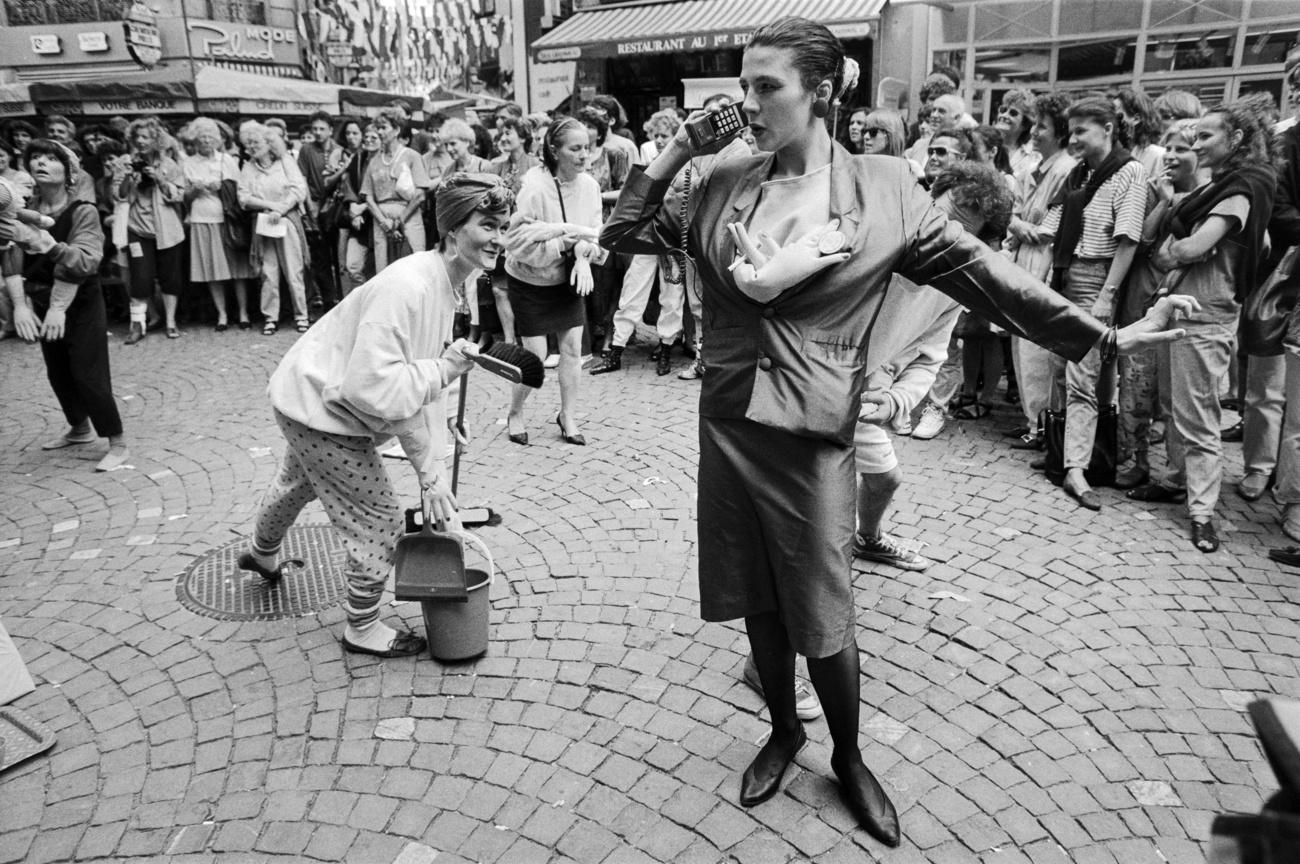

On June 14, 1991, half a million women in Switzerland joined the first women’s strike. Now, nearly 30 years later, they’re mobilising again.

Many people in Switzerland were taken by surprise on that spring day in 1991. The idea came from a small group of women watchmakers in the Vaud and Jura regions. Organised by trade unionist Christiane Brunner, it became one of the biggest political demonstrations in Swiss history.

About 500,000 women throughout the country joined in the women’s strike through various types of actions. They called for equal pay for equal work, equality under social insurance law, and for the end of discrimination and sexual harassment.

Why 1991?

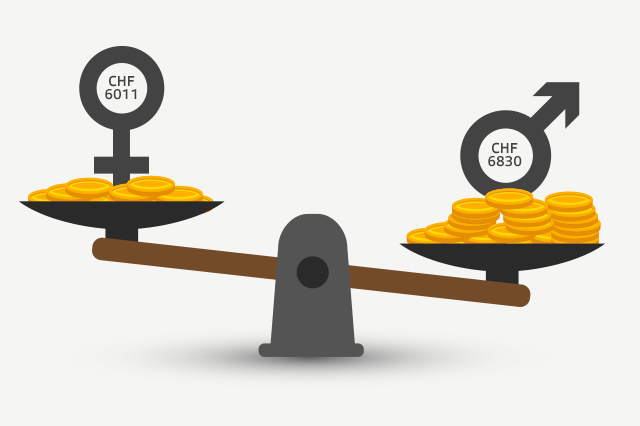

The choice of date was not arbitrary: on June 14 a decade prior, Swiss voters had approved a new article in the constitution on equality of the sexesExternal link. But the principle laid down in the constitution had not been translated into concrete legislation. The gap between men’s and women’s pay was still glaring.

The 1991 strike was also intended to mark the 20th anniversary of women getting the vote at the federal level, a goal achieved very late in Switzerland compared to all other countries in Europe and most of the world.

Why a strike?

The idea of presenting the mobilisation of 1991 as a strike at first struggled to find acceptance. “At the outset, the Swiss trade union congress was not enthusiastic,” recalls historian Elisabeth Joris, who specialises in women’s and gender history in Switzerland. “The word was going round: ‘This is a day of action, not a strike’, because the very notion of a strike was linked to paid work, while women worked in very varied settings and often not for a paycheque.”

On the other hand, talking in terms of a strike took on a highly political significance. “Every social movement takes place in a historical context, it is linked to other events,” notes Joris. Declaring a nationwide political strike meant appealing to the precedent of the other great nationwide political strike in Swiss history: the general strike of 1918, which included women’s suffrage among its demands, and in which women played an important role.

“Women were borrowing a tradition from the workers’ movement, but gave it a wider meaning, transforming and adapting it to the needs of the feminist movement,” explains Joris. The idea of a women’s strike was not new, either. In 1975 there was such a strike in Iceland, to mark International Women’s Year. Even the choice of March 8 as International Women’s Day commemorates the strike by New York garment workers in 1909 and 1910.

More

Minding the gap between the sexes in Switzerland

A different kind of strike

The 1991 strike movement had many obstacles to overcome. In the economic and political world, there was much opposition. At the time, Senate President Max Affolter urged women not to get involved in it and risk “forfeiting men’s goodwill towards their aspirations”.

On the other hand, the varied working environment of women, often outside the realm of paid work, did not lend itself to traditional forms of mobilisation. “The 1991 women’s strike involved a wide range of actions,” points out Elisabeth Joris. “This was able to happen because the strike was organised on a decentralised basis, unlike traditional strikes.”

Snowballs for politicians

Even if its historical significance was not recognised at the outset, the 1991 strike had a decisive impact on progress regarding equality of the sexes and the struggle against discrimination in Switzerland. The newfound strength of the women’s movement showed itself in 1993, when the right-wing majority in parliament declined to elect the Social Democratic Party candidate Christiane Brunner to a seat in the Federal Council, preferring a man.

“The majority in parliament thought it could do the same thing it had done ten years before with Lilian Uchtenhagen [another Social Democrat who failed to win the election]”, notes Joris. “But Christiane Brunner was the women’s strike. The reaction was immediate. A few hours later, the square in front of parliament was full of demonstrators. Some parliamentarians found themselves pelted with snowballs.”

Francis Matthey, the candidate elected to the Swiss executive branch, came under such pressure from his own party as well as demonstrators that he felt obliged to resign. A week later Ruth Dreifuss was elected in his place. “Since that time, the idea of there being no women in cabinet is just not acceptable.”

In 1996, legislation was brought in to ensure the equality of the sexes, which had been one of the demands of the strike. In 2002, Swiss voters approved legislation legalising abortion. In 2004, the article in the constitution on maternity leave, which had been in the constitution since 1945, was finally implemented in a piece of enabling legislation.

‘A new generation that favours feminism’

And yet, in spite of the victories of the women’s movement, equality remains a burning issue. Pay gaps between women and men remain considerable. The #metoo movement has brought to the fore – like never before – the issue of sexual harassment and discrimination based on a person’s gender or sexual orientation.

“Already around the 20th anniversary there was talk of another women’s strike, but the idea didn’t take hold,” notes Elisabeth Joris. “To succeed, a movement needs an emotional energy to it. This energy has now accumulated. There is a huge generation of young women in their 20s and 30s that favours feminism.”

“In 2019, we are still looking for equality, and realise that there has to be a lot more than this – the culture of sexism is part of everyday life in Switzerland, it’s invisible, and we are so used to getting along that we hardly notice it is there,” says Clara Almeida Lozar, 20, who belongs to the collective organising the women’s strike at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne.

Launched by trade unionists and feminists at the time of the debate on the revised legislation on gender equality, the idea of another women’s strike on June 14, 2019 was taken up in January last year by the women’s assembly of the Swiss Trades Union Congress External link. Apart from unions, the event is supported by Alliance FExternal link (an alliance of Swiss women’s organisations), the Swiss Union of Catholic Women External link, the Protestant Women of SwitzerlandExternal link and the Swiss Union of Farm and Rural WomenExternal link. The strike has adopted the motto “pay, time, respect”.

More

Swiss women’s ‘absurd’ struggle hits the big screen

(With input from Marie Vuilleumier; translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.