Is the time ripe for peace in Ukraine?

Limited gains on the battlefront, efforts to replenish arms stocks and bids by countries from the Global South to mediate between Russia and Ukraine may all be signs that conditions are nearing ripeness for possible peace negotiations, says Thania Paffenholz, executive director of Inclusive Peace.

Last month Geneva-based thinktank Inclusive Peace published a reportExternal link that offers a possible path on how to negotiate peace in Ukraine. It is based on current and historical research, and what the track towards negotiations could look like.

The report comes as the war drags on to its 19th month and has reached a near stalemate on the battlefield. On the ground — and further afield — casualties are mounting amid a global cost-of-living crisis due to disrupted food and energy markets. But while peace negotiations may not represent an option for some, others say signs are emerging that their time may soon be ripe.

In August an interview in the NZZ am SonntagExternal link cited Thomas Greminger, the Swiss head of the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP), saying that Switzerland could encourage dialogue between Russia and Ukraine without necessarily acting as an official mediator and play a role in hosting any talks. He also said Western nations needed to consider other plans than indefinitely supplying Kyiv with military support that would include Russia. Such a plan would include a ceasefire, followed by discussions on territorial claims, the ultimate political conundrum for both parties.

Pierre-Alain Eltschinger, a Swiss foreign ministry spokesperson, wrote in an email to SWI swissinfo.ch that any mediation “depends on the conflict parties agreeing on a third mediating party”.

The Centre of Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) in Geneva, as well as the GCSP, have both been involved in private diplomacy, such as ahead of the grain deal which allowed for food and fertilisers to leave Ukrainian ports; they have kept channels of contact open with the two warring parties, in order to set the stage for any talks.

More

Goodbye (Swiss) neutrality?

While Turkey gained international clout from the role that it played in the grain deal, other countries in the Global South have also engaged as intermediaries between Russia and Ukraine. In June an African peace mission led by South African president Cyril Ramaphosa that included representatives from seven other regional countries headed to Moscow and Kyiv.

During a press conference in June, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky told the visiting dignitaries that he would not negotiate as long as Russia continued to occupy Ukraine. Senegal’s president Macky Sall responded by saying “We do understand, Mr. Zelensky, your position because your country is occupied, and for you, military action is a way out of the situation. But we are thinking that when you’re fighting, you still probably need to have a place for a dialogue.”

At the UN general assembly on Wednesday Zelenskyy pushed once again for his peace plan and met with Brazilian president Luiz Ignacio Lula to discuss a way out of the war.

Brazil, China, the United Arab Emirates and Israel have also expressed an interest to mediate talks.

Paffenholz describes the various types of signals we should be watching out for for negotiations to become a reality.

SWI swissinfo.ch: Do you see any opportunities for a break in the fighting to allow any peace talks to begin?

Thania Paffenholz : Some experts say certain criteria are required for what they call ripeness for resolution. The most important is achieving a military stalemate on the battlefield. That is pretty much what we are seeing now. Military experts have predicted that the stalemate may last much longer than even this year, and may go way into next year. Another issue is fatigue in public attention and public support.

Last year it was impossible to even talk about the likelihood of negotiations. The situation was so polarised, and anything other than a military solution was inconceivable. That has changed, with a number of initiatives, such as when Turkey began focusing on the Black Sea Grain Initiative. Sometimes things begin with something tangible like that before something more may come from it.

A number of discussions regarding mediating negotiations have also been made more recently by the Global South, by Brazil, South Africa, China, and by a delegation of African leaders. The Global South became suddenly involved due to their concerns over the rising cost of living.

Another development that we are seeing is that President Zelensky is lobbying for his peace plan. Conversations began in DenmarkExternal link, then went on in RiyadhExternal link, Saudi Arabia, with the next round of conversations regarding the plan expected in autumn, to be hosted in Europe. These conversations may not get much media coverage, but they are proceeding.

SWI: You mentioned the issue of waning public interest in the war in Ukraine. With campaigning for the US presidential elections getting started, some politicians have said that they would not be interested in supporting Ukraine. Could this present a threat or an opportunity for peace negotiations?

T.P: The American presidential elections are certainly a key factor. If you talk about negotiations, you are clearly in the Republican camp. But some Democrats are also having thoughts and developing ideas about potential negotiations. It is difficult to address this because in Congress or for other decision makers the issue has become so politically polarised.

Imagine that the Republicans win the elections, and then they announce a plan to stop supplying arms to Ukraine. With the United States being the country’s biggest weapons supplier, if the arms supplies stop, there will be moves. Often it is not so much the realities that determine what happens, but the perceptions. Already now, the perception is that if the Republicans win, there will be a massive shift of Western support that will definitely affect NATO’s planning for military support. The closer we get to election campaigning, the more we may hear discussions about negotiations emerging alongside military engagement.

More

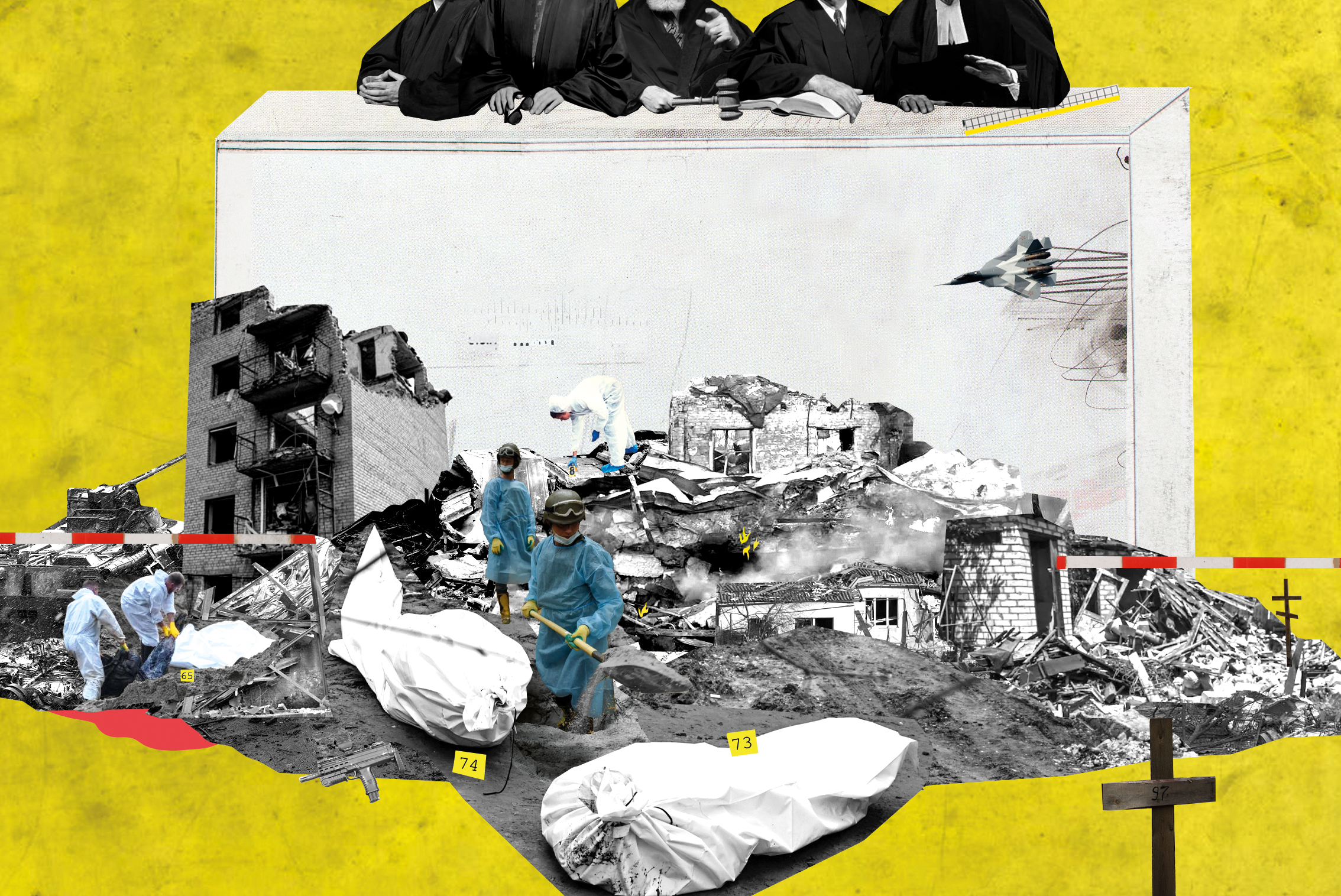

The challenges of bringing Russian war crimes to justice

SWI: Some people question whether the death last month of Yevgeny Prigozhin, the head of the Russian private mercenary Wagner Group, may have an impact on developments, due to the key role it played on the battlefield. Meanwhile both sides appear to be scrambling to replenish their arms supplies. North Korean leader Kim Jong-un has met Russian President Vladimir Putin, while British defence firm BAE Systems said it set up a deal to produce arms in Ukraine. How do you view those developments?

T.P: What is very normal in wars is that parties try to keep up fighting to make gains, especially when the conduciveness for potential negotiations is in the air. We usually see a rise in military activities as both sides seek to gain as much territory as possible to come equipped to the negotiation table. What we are also seeing here is that both sides are trying to keep up by getting more supplies, which also signals the military stalemate, as neither side is moving very much. From what we know, we are talking about tiny territorial gains and tiny losses.

Where the Wagner Group now stands is a big question. Whether it implies a destabilisation of Russia is all guesswork, even for the analysts. The issue regarding Prigozhin’s death is more of a concern to Africa for now, because Wagner is so powerful in Mali and other countries and entire governments relying on Wagner for their own security. In Ukraine, Wagner troops are still there, but under which rule? Will they stay in Ukraine? I think that’s a big question.

SWI: Is there a role that Geneva and its international organisations could play in this process? For instance UNCTAD, the UN Conference on Trade and Development, has been key in negotiating the Black Sea Grain Initiative.

T.P: What we suggest in the study is that because of the complexity of the war, we may see different negotiations on different topics take place, maybe even in different spaces. You may have conversations about the grain, others on the war’s environmental destruction and what can be done, as well as discussions on rebuilding the country. You may have concerted conversations on integrity and sovereignty, and talks about security issues and a ceasefire. There will be all sorts of topics that will come up and will be shaped at the time. One could imagine that all of these different topics may have different actors involved in shaping the agenda and developing proposals.

Within the expert community that we are part of, institutions and governments like the Swiss government or various UN agencies may have a role within those particular thematic conversations. We don’t see a big UN-led comprehensive peace process like in the past. This is interestingly in line with the UN Secretary General’s new Agenda for Peace, where he spells out the new geopolitical dimensions and points to the fact that going forward, the UN will have a supporting roleExternal link in discussions on difficult issues, as opposed to a leading role. I think this is most probably what we will see here.

Edited by Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.